What The ‘Most Wanted Iraqis’ Deck Of Cards Can Teach Us About War

As the notorious deck turns 15, an Iraq vet reveals the untold history behind it… and its impact on the … Continued

As the notorious deck turns 15, an Iraq vet reveals the untold history behind it… and its impact on the American way of war.

I. ‘Don’t go too far off the reservation’

“I was on my way to the Pentagon that morning, meeting up with my business partner, Jay, and pitching the need for the defense industry to embrace unmanned systems. I was late. I’m never late. I arrived just minutes after American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the western side of the building.”

Hans Mumm has a history of military service in his family, and although he was going to the Pentagon as a civilian on September 11, 2001, he also served weekends as a reservist just across the river. In fact, he was nearing the end of his eight-year reserve enlistment. But from the moment he smelled the burning jet fuel, he told me, his father’s words were a constant din: “You owe this country something. You must find a way to give back, to serve.” His father raised him to this standard because his father had narrowly escaped Hitler’s Germany in World War II.

Mumm was a seasoned non-commissioned officer, and his boss felt he would be more useful to the mission if he was a lieutenant. Within months, Mumm received a rare direct commission; by the beginning of the Iraq war, he had been activated to support the Defense Intelligence Agency. Mumm’s intellect and lively personality preceded him, as he was greeted with the warning by his new chain of command: “Don’t go too far off the reservation.”

Mumm’s team was told to focus on updating the database of the Saddam regime’s senior officials and influencers who would become high value targets. That wasn’t a problem: They had identified approximately 50 of Iraq’s “most wanted.” But that information was confined to the military’s classified intranet. It wasn’t in the hands of U.S. warfighters on the ground. It appeared that no one had formulated a plan on how to do this.

In time, their work would become a kitschy collector’s item whose biggest impact was on the American public, not the warfighter.

The war had already begun. Mumm’s team was behind. So, he told me, the members brainstormed: “How could we get this information downrange without requiring the warfighter to sit behind a classified computer?” Although young, the team’s members had all been around the block at least once — from Sgt. Scott Boehmler’s tour in the Balkans, where he was Gen. Wesley Clark’s favored targeting analyst, to the keen instincts and common sense Spc. Joseph Barrios brought from his day job as a Philadelphia police officer. The team didn’t want to push out another “bullshit intelligence product that nobody was going to read,” Mumm said.

This became the genesis of their big idea: an easily transportable intelligence product intended to educate the troops, in their leisure time, on their top military priorities. But in time, their work would become a kitschy collector’s item whose biggest impact was on the American public, not the warfighter. They would craft an accidental information operations campaign.

II. We won, right?

My pillow was a stiff green canvas bag that stored my gas mask. We had prepared for Saddam to use chemicals on us.

As an information operations analyst, the work I provided in the spring of 2003 emphasized messages and themes that purported liberation — not occupation. On that first deployment, several members of my unit were sent back home to Ft. Bragg after just a handful of months into the conflict because, well, the mission was accomplished. We won, right?

The prevailing view is that we lost. Last month marked the 15th anniversary of the beginning of the Iraq War. Much of the discussion centered around loss — of lives, money, stability in the region, and credibility as the world’s superpower. Those chemicals we’d feared Saddam might use on us in 2003 are the same chemicals being expended today on innocent men, women, and children in neighboring Syria.

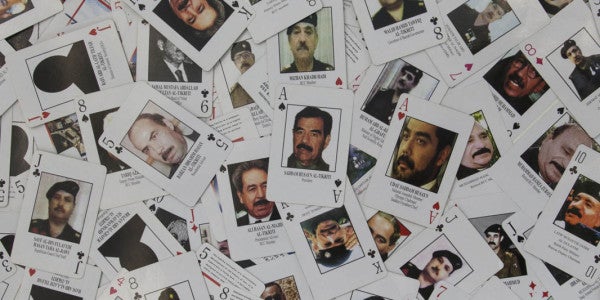

War is not a game. Those of us who went know this well. Yet our country latched on to this mindset early on — and one factor was the “Most Wanted Iraqis” deck: playing cards with the faces and names of high-ranking Iraq regime officials that U.S. forces were charged with capturing or killing.

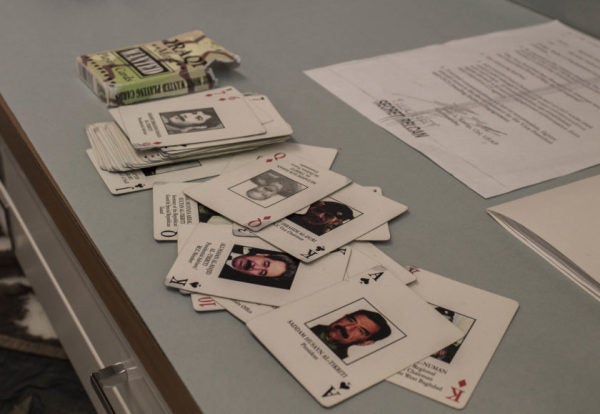

Graduate students from University of New Orleans public history department tour the Louisiana National Guard Museum April 11. A stack of playing cards displaying Iraq War’s “most wanted” rests on a shelf in the museum’s archive department.U.S. Army/Sgt. Karen Sampson

I knew nothing of this furor at the time. I was wearing the same clothes and sweat that I’d had on for weeks, serving in the cauldron of the Middle East. And I was dutifully completing one of my tasks in a filthy tent held down by sand bags—which was printing, cutting, and rubber-banding the decks of cards so they could be disseminated to operators moving forward across Iraq.

In recent years, media have covered what happened to the Iraqis featured in the deck, as if measuring these outcomes will tell us something about our success or failure in this war. Much less has been written about the team that created the deck back in Washington, where the air is fusty in windowless offices.

III. Just make a field manual

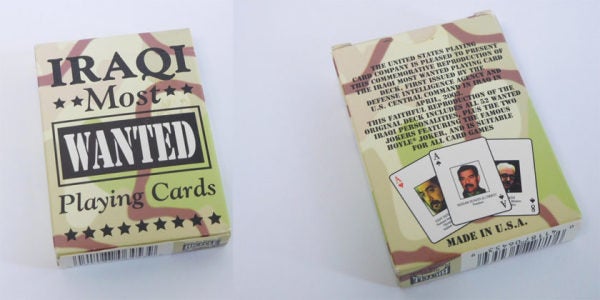

Mumm’s team quickly grew enamored with the idea of a card deck, a tool troops might actually use in their down time. There’s a rich U.S. military history of cards used this way,from the Civil Warto the Army Air Corps’ much-sought-after (and much-mimicked) World War II deck, whose cards feature silhouettes of German and Japanese fighter and bomber aircraft.

This was 2003, just before the dawn of social media. The team never anticipated its cards would be on the nightly news — or become a popular rallying point for the war. Their intended audience was, unequivocally, the warfighter. The team did not aim to minimize the gravity of war or perform information operations on the American public. Besides, they knew their doctrine: Targeting the American public is illegal. They weren’t opposed to pushing limits, but they respected sacrosanct boundaries like that. Mumm was slapped with a counseling statement and placed under investigation for the money he’d spent at the print shop.

Boehmler scanned Mumm’s basic Bicycle deck of cards from home, and before long, they were all downstairs in the DIA’s print shop, where they charged $78 dollars to their unit’s account and watched 200 decks roll off the printers.

Wikimedia Commons

Instead, he was slapped with a counseling statement and placed under investigation for the money he’d spent at the print shop without approval.

Things were looking extremely bleak for Hans. His team was harshly reprimanded, and the remaining decks were gathered up.

IV. The hand you’re dealt

Demand for the cards became insatiable. Bicycle Playing Cards grossed tens of millions of dollars from sales, since the original cards the team scanned captured their trademarked Joker. In the first week alone,the company claims, it sold 750,000 decks. The Defense Department hastily posted a printable card-deck file on its website to accommodate the barrage of requests. That spawned a slew of opportunists selling the decks for profit.

Back in Iraq, my unit did not have time for the Pentagon to print and ship the decks, so to expedite copies downrange, we printed on our forward operations base. Instances where the cards led to a direct mission success are difficult to find, yet the novelty of the deck left its undeniable mark on the troops.

The craze had other consequences. Mumm’s team, he said, recognized that putting Iraqi “HVTs” on cards would help dehumanize them. That could help the warfighter in battle; the team believed it would be better for the warfighter to know the cards’ faces by suit, not by name. “As people started to get captured, they wouldn’t say who the person was that got captured,” Mumm had explained to a defense reporter as the cards caught on in mid-2003. “They’d say, ‘They captured the 6 of diamonds out of the deck of cards.’”

They never anticipated that American news media would follow suit, often referring to the most wanted Iraqis by their card number; when the Associated Press reported on the deck’s existence in April 2003, its story began: “Odai Hussein is the ace of hearts. Qusai Hussein is the ace of clubs. The ace of spades, naturally, is their father, Saddam Hussein.”

The team later created a similar flip-book and posters for use by warfighters. Every member of the team was promoted — except Mumm, who instead was rewarded by having his negative counseling statement ripped up. And before the team deployed into Iraq, a few weeks after the cards had gone viral, they were honored with a citation for the “most successful information operations campaign in the history of DIA.”

Every member of the team would go on to serve multiple deployments. They attended each other’s weddings, moonlit with different organizations in the intelligence community, and even survived enemy contact together. Hans Mumm eventually took a medical retirement and has served at the request of the Director of National Intelligence.

V. We will be in Iraq in 15 more years, too

Like the military more broadly, Hans Mumm’s team demonstrated its ability to be nimble in war, where an innovative spirit and irreverent pursuit to deliver carried them through — even when leadership, policy, or vision failed to keep pace with the action. They won their battle, even when a larger victory seemed elusive. And even then, their small win had big unintended consequences for the war in Americans’ minds.

We need to apply that unconventional ingenuity to notions of victory and loss, too. As we learned in counterinsurgency warfare, in order to win, you can’t focus exclusively on the enemy. Despite the “Most Wanted Iraqis” deck’s grip on the American collective psyche, winning or losing the Iraq War was not as simple as crossing off the people on playing cards. The Iraq War’s legacy cannot just be measured by WMDs, 50 enemy faces, or Iraqi elections. Understanding the story of the warfighters, and so many others affected by war, allows us to look over the horizon.

We will be in Iraq for 15 more years if we don’t address the troubling truth that less than 1% of our society has fought this war, year after year after year. They slept with their heads on the bag of a gas mask, wrote final letters home, and went into this war with the belief that you go to war to win.

They are still there.